The chamber was stuffed, top to bottom, with artifacts and puzzles that shouldn’t have survived together. It raises a simple, unsettling question: why was so much meaning packed into one silent room?

I watched the dust float like slow snow as the stone plug finally shifted. Gloves squeaked. A low cheer died into a hush, the kind people give old places. Headlamps slid over carved walls and something metallic winked back, then another, then more than anyone wanted to count.

We’ve all had that moment when a door creaks and you know you’re not supposed to be there. This felt like that, but gently granted. The team leaned in, breath clouding the cool air, as if a story might fog the walls and reveal itself. The room felt too full to move. One thought kept looping. The tomb was full.

Inside the sealed chamber

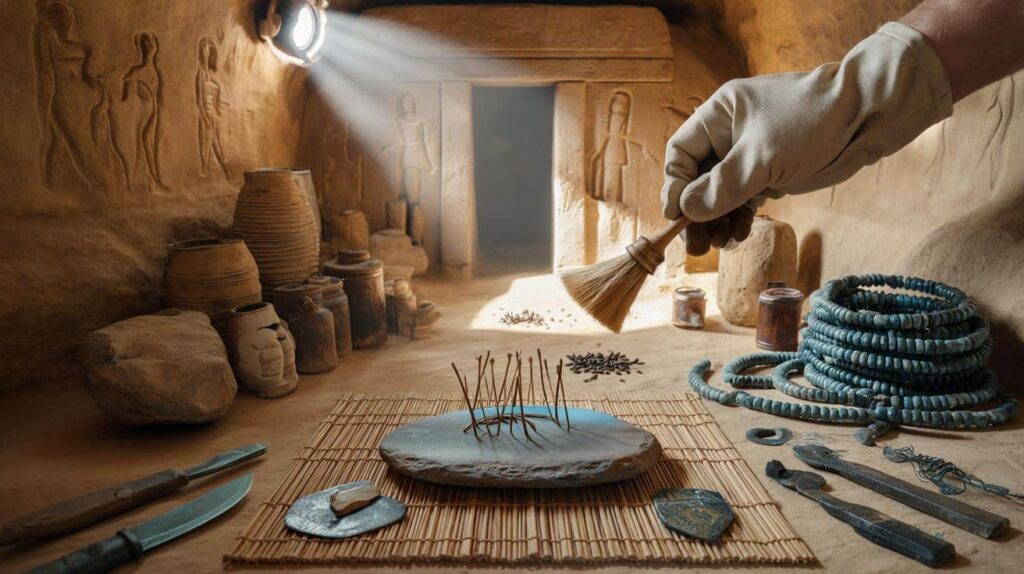

The chamber was wider than the trench suggested, a rectangle cut with almost stubborn precision. Light crawled over stacked vessels, stone figurines, copper tools, and a cascade of beads coiled like river weed. You could see thumbprints in clay. You could smell resin.

On the left, a bracelet sat on a flat stone as if someone had just set it down. On the right, a reed mat held a cluster of bone pins, their tips still sharp enough to raise a careful eyebrow. A field note landed quickly: 217 distinct items visible at first sight, not counting shadows.

What surprised the team most was the mix. Local limestone rubbed shoulders with lapis lazuli from far mountains, and copper that likely rode in from another valley. That’s the quiet headline: movement. Trade routes, promises, rituals crossing frontiers. A high-status burial, yes, but also a map of early courage.

Clues hidden in plain sight

Archaeologists read a room like this in slow motion. They grid the floor into palm-sized squares and peel time in micro-layers with brushes finer than a makeup kit. A camera on a rail takes hundreds of overlapping photos for 3D models, the tomb rebuilt digitally before a finger moves a bead.

It sounds fussy until you realize how often a hasty hand can erase a century. Dust is evidence. Pollen is a diary. Even the way a jar leans tells you if a body shrank under it or if a tremor nudged it sideways after a storm. Let’s be honest: nobody does that every day.

We picture discovery as a shout. In reality, it’s more like listening. A blackened residue could be bitumen or ancient honey. A smear on stone might be oil from hands, or from a funeral flame quivering across the floor. *Patience isn’t a virtue here, it’s a tool.*

How archaeologists work the miracle without breaking it

There’s a method to this level of restraint. The team stabilizes micro-climates first: humidity, temperature, and airflow, because fragile materials crack when the room suddenly meets the modern world. Tiny foil tents go up around vulnerable clusters. Cotton swabs take sneaky samples. Then, and only then, does a brush travel a single line.

A common mistake is focusing on the “shiny thing” and missing the context that gives it meaning. Another is touching objects before photographing them in situ, losing the original choreography of the room. The lead conservator laughs gently when visitors ask for the big reveal. The big reveal is a thousand tiny choices.

One archaeologist put it plainly:

“We’re not just excavating objects. We’re excavating decisions—why someone placed this bead here, why this jar faced the door, why the last act was to seal it all with care.”

- First pass: full-room photogrammetry and lidar sweep, no contact.

- Second pass: micro-excavation by quadrant, samples bagged and labeled before movement.

- Third pass: 3D reconstruction tested against notes, so nothing gets “invented” by memory.

- Final pass: removal in reverse order of placement, respecting the room’s original rhythm.

What the objects whisper

One copper blade shows a repair line, a careful hammering that suggests the owner kept it close. A ceramic jar bears a fingerprint that repeats on three other vessels—maybe the same potter supplied an entire lineage. Beadwork threads together materials from two rivers apart. This isn’t a hoarder’s stash. It’s a life edited into a room.

The burial pattern hints at a person who sat at the hinge between worlds—ritual and trade, kin and clan, dawn and dusk. There’s a carved seal that might be administrative, and a bowl with char clinging to its lip like a goodbye. When the team says “status,” they mean responsibility as much as wealth. Meaning isn’t measured only in gold.

Some pieces feel like messages from the people outside the tomb. A child’s toy of fired clay, clumsy and perfect. A scattering of seeds near the threshold, maybe symbolic, maybe lunch interrupted. The walls carry incisions that look almost like walking figures—close enough to guess, far enough to doubt. Doubt belongs here. It keeps the science honest.

What changes when a room like this opens

Finds like this reset timelines and get old debates moving again. Early urban life looks suddenly more networked, more musical, more human. Textbooks catch up slowly. The lab work won’t dazzle on camera—DNA swabs, residue analysis, radiocarbon dates—but it stitches loose threads into something wearable.

We’ve all had that moment when a familiar story begins to tilt. This tomb does that. Maybe the people we’ve been calling “proto” were already global in their own way, feet planted, eyes far. The room is saying: we were in conversation with places you think we couldn’t reach.

There’s also a softer shift. The person buried here was loved. You can feel it in the extra care, in the way a mat was smoothed twice, in the small mistake left just inside the door—a dropped bead, a heartbeat of grief. Archaeology often pretends at distance. In a chamber like this, distance collapses.

The questions we’re carrying out into the sun

What do we call the owner of this room without imposing our titles? Leader, artisan, keeper? If the materials span valleys, who traveled and who traded? And what song did the seal carry—authority or a whisper of trust?

The next months are the hard part. The chamber will be recorded, dismantled, and rebuilt in data, piece by piece, until the team can put the room back together with their eyes closed. New stories arrive slowly, and they stick better when they take their time.

Objects aren’t just things. They are rehearsals of touch, memory stored in shape, proof that someone woke before dawn to make something that would outlast them. Share the photos when they come, argue about the theories, and keep a bit of wonder for the quiet work you’ll never see. The room had waited 5,000 years. It can wait a little longer while we learn to listen.

| Point clé | Détail | Intérêt pour le lecteur |

|---|---|---|

| A sealed chamber intact | Room packed with vessels, tools, beads, and carved walls kept in stable air for millennia | Rare chance to read a life and a culture without modern disturbance |

| Mixed materials hint at networks | Lapis, copper, local stone, and organic remains found in one coherent context | Shows early long-distance exchange and complex ritual economy |

| Method over spectacle | Micro-excavation, 3D mapping, climate control, and layered documentation | Reveals the hidden craft behind discovery and why it protects meaning |

FAQ :

- Where is the tomb located?Researchers are keeping the exact location under wraps to protect the site. It lies in a dry plateau region where preservation is often exceptional.

- How old is “5,000 years” in calendar terms?Roughly late 4th to early 3rd millennium BCE. Precise radiocarbon dates will narrow the window once lab results return.

- Was there a body inside?Human remains appear to be present, likely in fragile condition. Analysis will clarify age, sex, health, and possibly kinship through ancient DNA.

- What’s the most surprising find so far?The blend of local craft with imported materials in a single, undisturbed setting. It suggests social roles that straddled ritual and administration.

- When will artifacts go on display?Not soon. Conservation and study come first. Selections may reach a museum after experts complete documentation and stabilization.