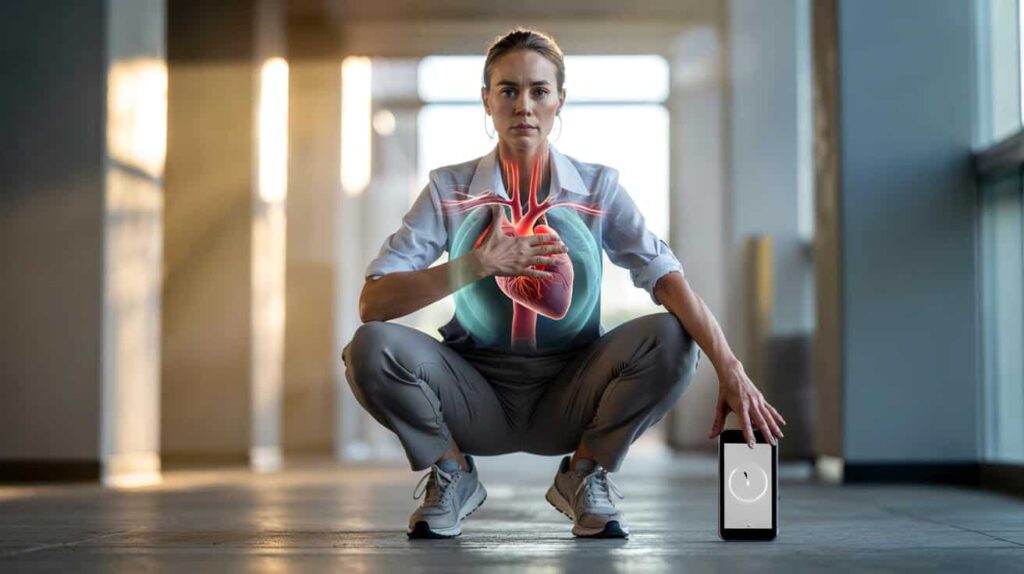

A brief minute, no treadmill, no lab coat. Just a low squat hold and your heartbeat. This small stress test can indicate how prepared your heart and lungs truly are, in a way your body comprehends: breathing and recovery.

A woman in office pants slid down a wall, knees bent, thighs shaking, phone timer ticking, hand on her neck counting beats. When the alarm beeped, she stood, closed her eyes, and observed her pulse decrease like a curtain falling after a performance.

Her breathing eased. Her shoulders relaxed. She appeared slightly surprised, then smiled as if she had been given a secret. *Your legs tremble, your heart races, and suddenly you learn more about yourself than a smartwatch ever revealed.*

One minute can seem lengthy. This one narrates a story.

The one-minute squat hold test, explained simply

The **one-minute squat hold test** is almost amusingly straightforward: hold a squat for 60 seconds, then observe how quickly your heart settles down. You don’t need a wall if your balance is good, but many prefer a wall-sit for stability. Regardless, the magic lies not in the burn. It’s in what occurs immediately afterward.

Here’s the basic flow. Take your resting pulse. Hold the squat for one minute at approximately chair-height depth. Stand up, note your pulse immediately, then count again one minute later. The decrease from “end of squat” to “60 seconds later” provides a quick snapshot of how well your system recovers. In physiological terms, that recovery is driven by the body’s brake system, your parasympathetic system.

Why does this indicate “how strong your heart and lungs are”? Because rapid **heart rate recovery (HRR)** after a small, controlled effort typically correlates with better overall **cardiorespiratory fitness**. It’s not a VO2 lab test. It’s a backyard signal with surprising significance. A higher HRR generally means your heart and lungs meet the demand, then ease off smoothly. A sluggish recovery may suggest that the engine and brakes require more training—or that you exerted a bit more than your current baseline.

What the minute feels like in practice

Imagine this: a teacher utilizes her lunch break to attempt the test in a quiet hallway. She slides into the squat as a microwave hums in the background. At 60 seconds, her quads are burning, her pulse is elevated, her breathing loud yet steady. She stands, counts 108 beats per minute, waits a minute, then counts 80. That 28-beat drop is impressive for her age and training, so she writes “28” on a sticky note. It remains on her desk next to a pen and a half-eaten apple.

On another day, a new parent tries it between washing bottles. The hold concludes at 45 seconds, not a full minute. Still valuable. Peak heart rate: 120. One minute later: 103. The drop is smaller, and the note reads “17.” There’s a hint of pride for attempting it at all, and a quiet determination to repeat it next week. We’ve all experienced that moment when a small number on a scrap of paper suddenly feels like a forecast for your future.

These numbers don’t judge. They trend. Repeat the test and they create a gentle graph of your recovery capacity. Over time, the hold becomes smoother, the breath less ragged, the recovery curve steeper. It’s the curve that counts. If a lab treadmill is a symphony, this is a humming tune you can carry with you every week, and still hear when you’re fatigued.

How to perform it, obtain a meaningful number, and avoid common pitfalls

Here’s the method that makes the test resonate. Warm up for two minutes with gentle marching and ankle rolls. Find a safe location. Lower into a squat or wall-sit with thighs roughly parallel to the floor, knees aligned over mid-foot, heels down. Start the timer. Breathe in through your nose, out through your mouth. At 60 seconds, stand tall. Count your pulse for 15 seconds and multiply by four. Wait one minute, count again. Your HRR is peak minus one-minute-later. Note three things: hold time, HRR, and how breathless you felt on a scale of 0–10.

Approach it with kindness. If your knees protest, use a higher squat or a wall-sit with a pillow behind your back. If you feel dizzy, stop. Let’s be honest: no one really does this every day. Aim for once a week, at the same time of day. Don’t pursue records—pursue consistency. The squat depth should be repeatable, not heroic. A minor change in depth can inflate the effort. Keep it honest, and the numbers will become reliable.

Think like a coach, not a critic. Start where you are and let the test meet you there. If your HRR is under 15 beats, that’s a prompt to build an aerobic base with brisk walks, easy rides, or swims. If it’s 25–35, you’re in a good rhythm. Over 35 after a full minute indicates a well-tuned engine, especially if your breath rating is around 3–4 out of 10.

“The hold is the bait. The recovery is the story,” as one exercise physiologist likes to say. “If the story improves, your life usually feels better too.”

- Quick scoring cues: HRR ≥ 25 beats = strong; 15–24 = moderate; < 15 = needs more base.

- Can’t hold 60 seconds yet? Record your best time, then use the same position next time.

- Track three things: hold time, HRR, breath rating (0–10). Trends are more valuable than single numbers.

- Knees unhappy? Go higher, shorten the hold, or switch to sit-to-stand reps in one minute.

- If you have a heart or lung condition, consult your care team before testing.

Why this small ritual endures

The test feels relatable. It fits between emails, before a shower, after dropping off at school. No login, no dashboards. Just a minute of focus and a minute of listening. You experience a tangible burn, then a quiet score that relates to your future hikes, stairs, and sprints to catch a train. It’s a clever trick that transforms discipline into curiosity.

It also creates a fairer reflection. Fitness can be loud—big lifts, long runs, sharp selfies. Recovery is quieter and often wiser. A better HRR typically results from easy, repeatable training that respects sleep and stress. Think of walks that gradually get longer, rides that conclude with a smile, short bodyweight circuits that leave you humming. The test nudges you toward those choices without preaching.

Most importantly, it grants you permission to start small and still gain something meaningful. The minute won’t provide all the answers. It doesn’t replace a VO2 max test or a clinician’s advice. It does offer you a pocket-sized compass you can check whenever life becomes overwhelming. When the number decreases, you take a breath. When it increases, you think, “Okay, what’s working?” And you continue.

| Key Point | Detail | Reader Interest |

|---|---|---|

| Measure heart rate recovery | Count pulse immediately after the hold and again at 60s; subtract | Simple indicator of recovery capacity |

| Keep the squat consistent | Same depth, stance, and timing each week | Makes trends reliable and comparable |

| Use a three-metric log | Hold time + HRR + breath rating (0–10) | Richer picture than a single number |

FAQ :

- How do I know if my heart rate recovery is “good”?Generally, a 25–35 beat drop after the minute indicates solid recovery for many adults; 15–24 is common and improvable; under 15 suggests you’ll benefit from more easy aerobic work. Age, medications, and stress can influence these ranges.

- Does a squat hold truly reflect heart and lung strength?It reflects how your system recovers from a small, steady effort. Faster HRR usually aligns with better fitness, though it’s not a lab test and doesn’t diagnose disease.

- Wall-sit or free squat hold—which is better?Use the one you can safely repeat. Wall-sits reduce balance demands and help standardize depth. Free holds engage more stabilizers but can vary more between sessions.

- How often should I repeat it?Once a week is sufficient. Same day, same time, similar conditions. If you’re unwell, underslept, or just raced, skip or note it—it will skew the number.

- What if my knees or back hurt?Go higher, shorten the hold, or switch to the one-minute sit-to-stand test. Pain isn’t a badge here. If discomfort persists, consult a clinician or physiotherapist before retesting.